Hi, I’m Gabrielle Blair and this is my newsletter. It’s completely free to access and read, but if you feel so moved to support my work, please consider a paid newsletter subscription: just $5/month or save money with the $50/annual sub. You can also go way above and beyond by becoming a Founding Member at $75. Or, some of you have let me know you’d rather send money directly via Paypal and Venmo (@gabrielle-blair). Thank you! Seriously, thank you. Support from readers keeps this newsletter ad and sponsor-free.

Most of the time our opinions change gradually, but once in awhile, we read something or learn something and have a MASSIVE shift in our thinking. I’m talking a full 180 degree shift. I’m not sure how often a huge, sudden shift in thinking happens for any one person, or even how often they recognize it’s happening, but I am very aware I’ve experienced one of those major shifts in thinking for two years in row. In 2020, my views on policing changed really quickly, and in a huge way. I went from assuming police were a necessary part of any society, to being fully on board with the abolish the police movement. (You can read my thoughts about that if you’re curious.)

Then, in 2021, I experienced a huge shift in how I think and feel about adoption. I’ve shared tweets and links about this from time to time, and whenever I share tweets that don’t paint adoption in glowing terms (or are outright negative about adoption), I receive many messages from readers who are disturbed about what they just read. Who in the world doesn’t like adoption? What does that even mean? You want kids to live in orphanages? My best friend is adopted and she loves her adopted family. I want to adopt someday and reading this is stressful!

And hey. I get it. I had the exact same thoughts until about year ago.

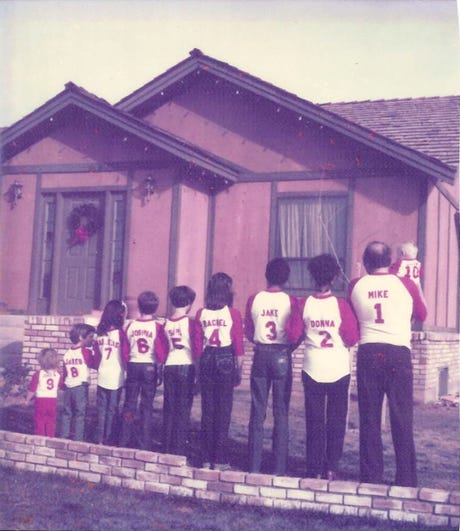

Adoption touches everyone. Maybe you yourself were adopted. Maybe you are an adoptive parent. Maybe you have an adopted sibling (I do! My oldest brother, Jake, was adopted by my parents when he was six, long before I was born — he’s number 3 in the photo above, I’m number 7). Maybe you relinquished a child for adoption. Maybe you are a grandparent of an adopted person. Maybe your closest friend is an adoptee. Maybe your spouse is an adoptee. Maybe you are infertile and are considering adoption to grow your family. Maybe your neighbor is raising adopted kids. Every person knows and loves someone who is closely affected by adoption.

So I’m going to tell you how my brain shifted on adoption, but I want you to understand, truly understand, that I am not out here judging anyone. If adoption is part of your life, I’m not writing this to you personally, and I’m not thinking of any particular individuals when I write this. Yes, adoption is deeply personal, but the problems with adoption are largely systemic. So I’m just going to explain how my own thinking changed. It might change your thinking too, or it might not.

For me, it started on Twitter. Someone I follow was interacting with some accounts that were using hashtags: #adopteevoices #adopteetwitter #adoptees. Since adoption touches my life (again, it touches everyone’s life), I was curious and started following the conversation. It was not what I expected. The people in the conversation were adult adoptees, who described good relationships with the parents who adopted them, while also arguing that adoption is harmful. The conversation surprised me because outside of a few essays warning about the white savior-ism that can happen in certain adoptive relationships, I’d never heard anyone talk about adoption-in-general with negative terms.

Adoption is Family Separation

The Twitter conversations I was reading centered on how harmful it is that when people were adopted as babies, they were cut off from not only their birth parents, but also their whole extended birth family — grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, and the whole family tree. It shook my brain up because I had never considered that. Obviously, I knew that adopted babies were often cut-off from their birth mother, but I had not considered the aunts and uncles, the cousins, the half-siblings and full siblings, the grandparents. I only had to picture my own extended family for a fraction of a second to feel the force of that loss hit me. To be cut-off from your whole extended family could never be anything but traumatic.

It reminded me of how frustrating and discouraging it is when those who are descendants of enslaved people try and do genealogy, and hit a dead end just a few generations back. Why a dead-end? Because enslaved people were so often intentionally cut-off from their birth families; stolen from their parents, communities and countries. It’s openly discussed how cruel that practice is, and how damaging it is for new generations to not have access to knowledge about their ancestors. Everyone would agree this is awful and unfair and one of many horrific legacies of slavery. And yet, cutting off people from their ancestries is a practice that still commonly happens today. When babies are adopted, it’s not unusual to cut all ties with the birth parents, which also means cutting all ties to the baby’s ancestry and extended family.

The grown adoptees who use the #adoptee #adopteevoices #adopteetwitter hashtags also talk about how the government endorses this cruelty and makes it official. In some (maybe all?) states, a baby’s original birth certificate is destroyed when they are adopted, and they are given a new one — one that is an outright a fabrication — which shows the adopted parents as the birth parents.

I thought I had a handle on how cruel this family separation is, but it hit home again when adoptees offered up this example: Imagine a couple, a man and woman who are very much in love and decide to get married. A few years later they have a baby. And when the baby is a few months old, the family goes for a happy Sunday drive. There is a car accident and the parents die, but the baby survives, unharmed. If the extended family couldn’t care for the baby, and the baby was adopted, would the adoptive parents erase the birth parents from that baby’s life? Would they rename the baby? Would they erase the grandparents and cousins from the birth family? Would the adoptive parents act like the birth family doesn’t exist? Or hide their names and photos from the baby?

The answer should seem obvious to everyone: of course not! The baby has already experienced something horribly traumatic — they lost their parents. No one would think to add trauma to the baby’s life by withholding their family history. No one would think that’s okay. And yet, it happens to adopted babies every day.

Adoption is Big Business

The next thing I learned from listening to adoptees is how much of a business adoption is. They explain that no one wants to think of it this way, but our current adoption practices have created a market that normalizes selling human babies. It’s a market that could never be free of corruption, because it’s literally adults selling human babies.

This aspect of adoption is something you may have heard about before. It’s been written about in some major publications, including Time magazine:

Problems with private domestic adoption appear to be widespread. Interviews with dozens of current and former adoption professionals, birth parents, adoptive parents and reform advocates, as well as a review of hundreds of pages of documents, reveal issues ranging from commission schemes and illegal gag clauses to Craigslistesque ads for babies and lower rates for parents willing to adopt babies of any race.

Part of the reason adoption is big business, is that adoption is expensive and there are people desperate to become parents who are willing to pay a lot of money for a baby. Adoption through private agencies costs $60,000-$70,000 and includes legal costs, birth-mother expenses, and other add-ons.

The costs of adoption bring up really hard ethical questions. Fact A: We know that one of the main reasons a person decides to relinquish their baby for adoption is because of financial struggles — the birth mother does not have access to enough money or resources to feed, clothe, house, and raise the child.

I’m not the first person to point out that America hates poor people, and that we love to punish people for being poor. Our current adoption practices are another vivid example of this: Oh, your life is really hard and you don’t have enough money to pay for a basic existence? Well tough luck for you, now we’re going to torture you further and pressure/force you to give your baby to someone with more money.

Fact B: We know that if the birth mother can access enough money, or some financial security/safety nets, in most cases they would choose to raise the child themselves.

Fact C: We’re learning more about adoption relinquishment trauma, and we know that babies who have a loving bond with their birth mother have the best outcomes.

This all brings up very hard ideas. If a couple is willing to pay $60k to adopt, and “they want what’s best for the baby”, wouldn’t giving financial support to the birth mother, so she could keep the baby with her, be “what’s best for the baby”?

If a couple adopts a baby and loves that baby so much that they “are willing to do anything for the baby” — willing to pay medical bills if the baby is sick, willing to feed and clothe and house the baby, willing to pay for lessons and activities to give the baby the best education — couldn’t they do all of that while letting the baby remain with the baby’s birth mother?

As humans, as communities, are we only willing to care for a baby if we “own” the baby? If the baby is “ours”? If and only if we get to name the baby?

Am I saying childless couples should give money directly to people who can’t afford to keep their kids? No. But also, sort-of? Maybe our taxes — everybody’s taxes — should go to programs that make sure whenever possible, children can stay with their birth parents. Maybe there should be volunteer programs where wealthy people are paired with not-wealthy people. Where they can be a rich aunt or uncle for a child in need, to lend financial support until the birth parent is financially stable; financial support that enables a family to stay together.

Side note: If you want to learn more about what it looks like for someone to give up their baby because of financial hardship, Little Fires Everywhere (reading or watching) is a good place to start.

If Not Adoption, What Then?

So what are adoptees saying? They think we should just get rid of adoption? This is the first question that comes to mind when we take a deep look at current adoption practices.

I can’t speak for adoptees, I can only tell you what I’ve learned from them. And what I’ve learned is that not all adoptees agree on what could/should replace adoption. Keeping families together is the priority, and in cases where that isn’t possible, one idea that comes up quite a bit is permanent guardianship. With permanent guardianship, a family can take in a baby or child and raise them in a loving home, without changing the baby’s name or their birth certificate, and without erasing the baby’s extended family. It looks and functions much like adoption, but removes any secrecy from the equation and doesn’t erase or hide identity. Another idea is making plenary adoption illegal, but keeping forms of open adoption — where the child’s birth identity remains intact — available.

This is also a good place to reiterate that there are plenty of adult adoptees who advocate against adoption, while also retaining good relationships with their birth families. And there are also adoptees who think the current adoption practices are generally fine. Adoptees are not one mass of people, and they don’t all think alike or agree on these topics.

Though everyone has opinions on this topic, I find I’m very focused on learning from adoptees themselves. It seems like pretty much any conversation about adoption that centers adoptive parents instead of centering the adoptee, is likely to go in the wrong direction.

Protecting Power & Whiteness While Shaming Women

The more I’ve thought about this topic, the more it’s become crystal clear to me: Our current adoption practices are rooted in a desire to shame and punish women for having sex, while protecting whiteness, and the reputation of men.

For centuries teens and woman who were impregnated but not married, were sent away to endure the pregnancy and childbirth in secrecy. Made to go through a really hard experience without the support of their loved ones and then told to hand off the baby and go back to whatever was left of their previous lives. All this to protect the “virtue” of the community, and the reputation of the man who impregnated her.

I appreciate how these ideas are laid out in this article about adoption in The Nation. A few excerpts:

…all of the stories we choose to tell about adoption—both politically, and for our entertainment—contribute to a predominant, largely unchallenged narrative of adoption as a social good. But this political and cultural consensus around adoption as a social good has ignored the history of private domestic adoption as a mechanism for maintaining norms of whiteness, class privilege, religion, and social order in the context of the family.

These adoptions were about policing women’s behavior and strictly upholding deeply rooted patriarchal ideas of sexuality, reproductive choice, motherhood, marriage, family, and power. Historian Rickie Solinger has argued that the prevalence of adoption in a society is, in a crucial way, a reflection of the vulnerability of women. Today, most women who relinquish infants for private adoption report wanting to parent but lacking the support and financial resources to do so.

Excerpt 2:

…the taking and transfer of children has been used as a tool throughout American history in the separation of enslaved African children from their parents, the forced removal of Native American children from their families and tribes, the policing of Black families within the child welfare system, and, of course, the removal of children from immigrant and asylum-seeking families at our border.

…that adoption is almost universally the transfer of infants from families with fewer resources and less power to families with more resources and more power…

It’s such a good article, and I think the authors, Gretchen Sisson and Jessica M. Harrison did an excellent job with this very sensitive topic — including acknowledging the things people often celebrate about adoption:

Adoption makes many queer parent-led families possible; it allows some adults to pursue single parenthood by choice; it can create familial bonds across racial, ethnic, and cultural difference. All of these types of families would have been radical a generation ago, and inconceivable a generation or two before that.

I hope you read it.

We also have to look at the patriarchy to consider why people are so desperate to adopt babies. Could it be because we’ve told women, for thousands of years, that their only value is their uterus? That if they can’t be a mother then they are worthless? That they aren’t allowed to do meaningful work outside the home because those jobs are reserved for men?

What if we as a culture instilled in childless people that there are so many ways to improve the world and the community that have nothing to do with parenting. What if people understood they have value simply by existing. That they can still thrive and be happy whether or not they choose parenthood?

As I said in the beginning, my thoughts on adoption have changed dramatically, and in this newsletter, I wanted to share what instigated that change. Outside of that sharing, I don’t have any action items for you — no dramatic requests or demands for change. Just a hope that we’ll all be interested in learning more; that we’ll set our assumptions aside, and be willing to listen to #adoptees and learn from their experiences.

That’s all for now. If you have any resources on this topic that you’d like to share, please do. I hope you’re having a good week.

kisses,

Gabrielle

I agree with so much of what you're saying. AND I am an adopted mother of seven kids, all adopted internationally. Six out of the seven were abandoned with no connection to any family history whatsoever. Not even names or birthdays. We try to honor their culture and are very open and honest about their histories and would encourage them as much as possible to find their birth families if they want. We would 100% support that. One son has some information about his birth mother and we hope to connect with her one day when and if he wants to.

Adoption is brokeness. We honor that. We acknowledge it and don't gloss over the fact that there is much pain involved on all sides. We hold that at the same time as knowing our kids have physically healthy lives and a family to support them and love them. All kids need families, this I 100% support. Not institutions to raise children, families. But instead of just pulling them out of the system we need to go upstream and see why they are falling in. That's where we'll solve the problem. And that is why I support so much of what you're saying here. Adoption is not the solution, finding out why it is necessary and solving that is.

Thank you for bringing attention to this issue! I wanted to add my perspective as a lawyer working in family defense, a field dedicated to reunifying families separated through the family policing system. Most domestic adoption is not of children whose parents have died or have chosen to put their child up for adoption; rather, these are children whose parents' rights have been terminated by child protection systems, often for minor infractions. I had one client, a nurse and loving father, who got into a fight with another adult man and was charged with neglecting his child. I'm not condoning fighting, but he cannot reasonably be said to have neglected his son. In other cases, parents who are unhoused are punished for their poverty by having their children removed, rather than the state providing housing. This system particularly targets families who poor and/or Black, effectively extending police surveillance in these communities.

For more information, see this NYT article: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/21/nyregion/foster-care-nyc-jane-crow.html

New York state lists children who are available for adoption, much like animals searchable by characteristics on PetFinder. This is a sickening concept, if we remember that almost all of these children have parents who would do anything to have their children returned: https://hs.ocfs.ny.gov/Adoption/Child/DemographicSearch